Subscribe now and get the latest podcast releases delivered straight to your inbox.

It’s an age-old cliche, but it bears repeating: television is not the same as real life.

This is a good maxim to keep in mind at all times, but I’m speaking here about the interviews we see on late-night TV.

The effortless banter, the smooth transitions, the perfectly set up punchlines? These are rehearsed.

Beforehand, guests work with producers to outline what’s going to be asked and said — and how they’re going to plug their forthcoming movie, album, or series.

Now, these interviews are not completely scripted, but there are certainly no surprises.

According to Quora user Scott Bromley, the planning “informs the bullet points that are written on an index card on the host's desk.”

I know, it’s shocking. You might even feel a little betrayed.

Let me share something else: When you read an interview in a magazine or on a website, those, too, are edited and condensed, sometimes heavily.

If it is your job to interview people at your company (or at other companies), perhaps as a content manager or otherwise, it is also your job to prepare those interviews for publication.

The task can be daunting, but I hope to help.

A definition of terms

For the sake of this article, keep the following definitions in mind.

Interview: A recorded conversation between a writer and a person of interest, used as the basis for a publication. I am excluding interviews that are made to be broadcast — that is, filmed or recorded for podcasts. These require a different set of rules and conventions.

Transcript: The exact written representation of a conversation. IMPACT uses Rev.com to turn an audio file into a transcript, but Temi is another cheap, fast option that uses computer automation.

Published interview: An edited, optimized, polished, digestible representation of an interview.

With any article, readers trust a writer to do some of the heavy lifting for them. That’s why articles need organization, smooth transitions, a conclusion that summarizes and inspires. A reader is expecting something cogent and complete.

Similarly, when someone comes to your site to read an interview, they are not expecting something that’s freewheeling, digressive, and vague. Rather, the published version should be engaging and comprehensible.

Thus, as you prepare an interview for publication, keep these five tips in mind.

1. Don’t think of a published interview as a transcript

A transcript is the systematic documentation of everything that’s said in an interview. You have a responsibility to your readers to take a transcript and make the content digestible.

At the same time, you have a responsibility to your subject to keep it genuine and authentic.

The balance between the two is the artistry that’s required.

According to Alison Beard, a senior editor at the Harvard Business Review and author of the Life’s Work section that appears inside the back cover, “conversation is messy, Q&As shouldn’t be.”

When describing her process for condensing a transcript, Beard says she does “lots of streamlining without changing the interview subject’s language or meaning in any way.”

What gets published should be “excerpts of the person’s best and most relevant points.”

Beard, whose recent interview subjects include Vera Wang, John Kerry, and Deepak Chopra, also acknowledges “I edit my questions down to a minimum,” suggesting that the interviewer's role is that of prompter, not interrogator.

Author and editor Lary Bloom agrees. “As to interviews,” he says, “it is the general practice to edit them for length, grammar, and [it] is sometimes the case to rearrange a bit where necessary.”

A conversation, according to Bloom, “naturally strays from the main points,” and “it’s not possible to use every word, nor would [your subject] want that.”

Bloom, who just published a sweeping biography of Sol LeWitt, continues: “The finished product should not contain any needless words. You have no obligation to include material just because it was said.” (the emphasis is mine)

2. You need to cut — probably more than you think

I recently trimmed a transcript significantly to prepare it for publication. In doing so, I boiled down my subject’s words to a more accessible representation of what he was saying — and removed tangential threads that felt oblique.

His trust in me (and his ability to edit the document after I went through it) allowed the process to work as it should.

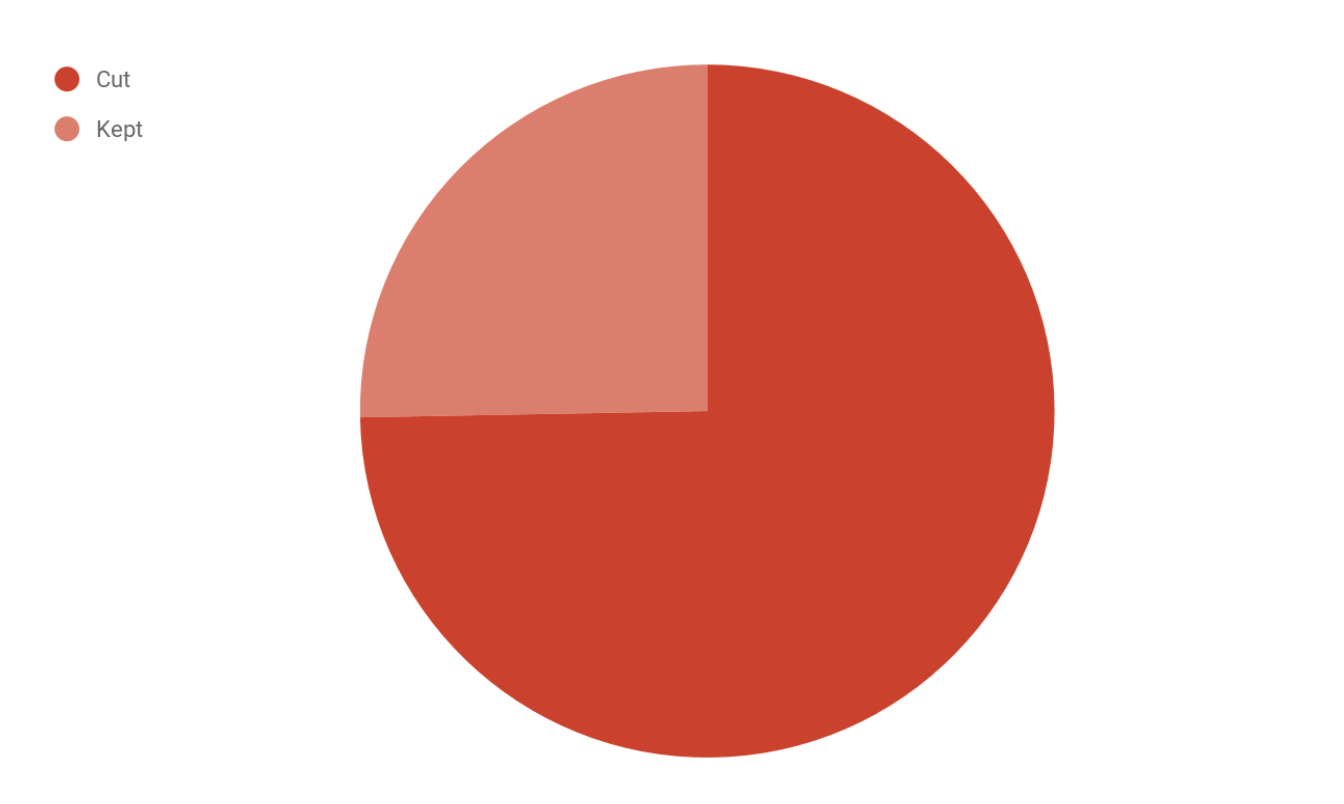

To be specific, I trimmed this transcript from 6092 words down to a published version of 2062 words. Think about that. Or, allow me to share a visual representation:

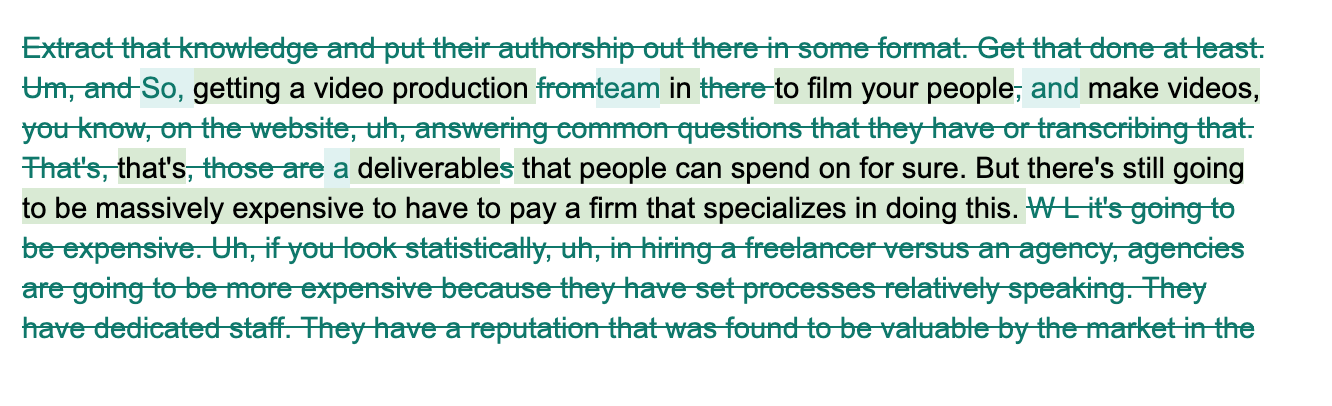

In practice, that looks like this:

In this excerpt above, I cut 90 words, kept 39, and added four to help clarity: so, team, and, and a.

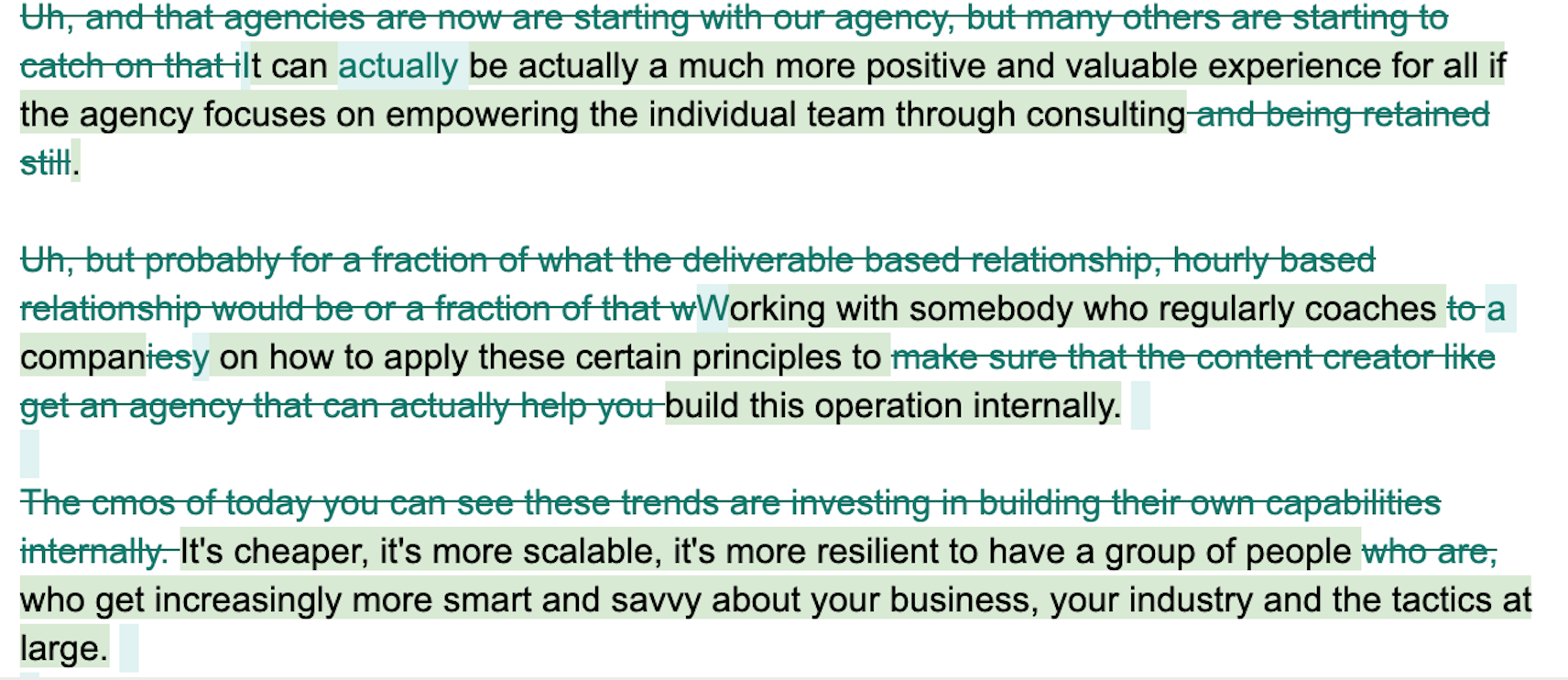

Now, this is an extreme example. The true story behind that pie graph above is that I cut a few whole questions and answers that didn’t end up being relevant to the discussion. Sometimes, whole sections were left intact. In many cases, my edits looked like this:

Try as you might, a conversation will never stay organized. A company leader or expert might veer toward another topic, tell an anecdote that doesn’t transfer well, or repeat herself. To serve your reader, you must be judicious. You must cut.

3. That can mean cutting yourself, too.

In a recent interview, I jumped in to share what I thought was a clever quip about the Rolling Stones. Of course, geriatric British rockers were far from the subject matter at hand.

Although it sometimes hurts to be reminded of this, people aren’t reading to hear you.

Your questions are there to organize your guest’s thoughts. To the extent that you can, trim your own words and questions so that they merely serve as prompts for your guests and organizers for your readers.

4. Sometimes you might need to need to reorganize

The same skills you bring to editing an article you need to bring to editing a transcript, especially for your business blog.

In a recent interview, my subject dropped in a particularly essential pearl of wisdom. Unfortunately, he did it in a context that didn’t really do it justice.

I moved the line to a different section.

Again, such edits should certainly be communicated to your subject.

Most interview subjects want you to help them sound their best — just as writers ask you to help them make their prose more precise, more readable, more engaging.

You must maintain their tone, intention, and meaning, but sometimes that can best be done with a slight reorganization.

Which brings me to my last point.

5. Your goal is accuracy — but also making your subjects look their best

Talk show hosts are good if they can make their guests appear all the more charming, witty, and clever.

Jimmy Fallon is widely panned for his forced laughter in interviews, but such a tactic is employed to make his guests seem funny and original (even if the interview has been rehearsed and Fallon is not genuinely moved to laughter).

You are interviewing your subject-matter experts so that they can share their knowledge with the world. Sometimes, their delivery might be more information dump than clear, cogent lecture.

In such a case, you may need to organize and optimize content to convey their information more clearly and more effectively than they did in speech.

Remember, a published interview is a digestible, condensed representation of your initial conversation. It’s up to you to convey the essentials to your audience in a way that presents your subject as the intelligent, well-spoken, astute person they are.

Trust your instincts, stay true to your subject, keep your reader in mind

It can be overwhelming to receive a dense, single-spaced transcript a few days after an interview. I tend to paste the whole thing in a document and color code it. Green are my questions, yellow are sections I’ve already edited, blue are sections that seem tangential.

Gradually, painstakingly, I work to piece together a published interview that is truer than the original conversation. Gradually, there’s more and more yellow. Superfluities get trimmed, crosstalk gets scrubbed out, points get made fully — and the beginning and end feel pointed and succinct.

With an okay from the subject, it’s now an organized, concise representation of your initial conversation that’s ready for publication.

Order Your Copy of Marcus Sheridan's New Book — Endless Customers!